Achieving Individual Goals…Together

A community’s purpose provides direction and delineates boundaries. Nevertheless, its members’ motivation to invest their energy stems from their desire to achieve their individual goals.

Fabian Pfortmüller at Together Institute has rapidly become one of my favorite writers on the topic of community. In a recent article, Fabian shared some typically apt observations:

Shared purpose is…an initial reason to say yes.

90% of people’s energy comes from their own personal interest.

We can either embrace it and design for it or ignore it (and pay the price in the form of superficial engagement.)

If we understand [members’] personal needs, we can choose formats and practices that help [members] advance their projects.

The organizers that seem to struggle the most with this are people who create communities under the umbrella of an established organization.

In other words, effective communities help us achieve our individual goals…together.

Audiences, Networks, and Communities

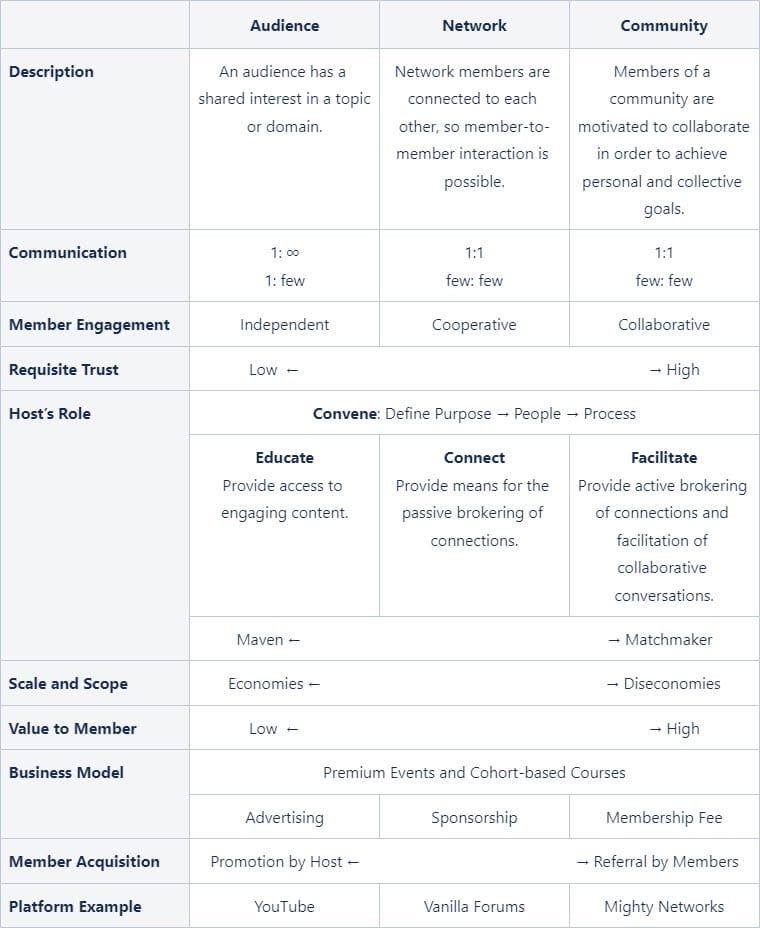

Let’s start with defining community. Here’s a summary of my understanding of the distinctions between an audience, a network, and a community:

Like Fabian, I am primarily interested in the conditions under which a community can thrive.

Purpose → People → Process

A community’s purpose determines the people who comprise it. In other words, purpose and people are inextricably linked. The processes underpinning the community should follow its purpose and people.

Purpose

As I’ve noted elsewhere, Gina Bianchini and her colleagues at Mighty Networks say,

The power of your community comes from people mastering something interesting together…Your Big Purpose is the motivation for your community. It’s something that can only be accomplished by bringing these exact people together…

Gina’s observation is reminiscent of a key point made by Priya Parker, the author of The Art of Gathering:

The art of gathering begins with purpose: When should we gather? And why?

The more closely the group’s purpose aligns with our personal objectives, the more likely we’ll be willing to engage and collaborate.

People

A statement of purpose is an articulation of direction and boundaries. Priya is crystal clear on that point:

People who aren’t fulfilling the purpose of your gathering are detracting from it.

For instance, the purpose of Faculty Resilience is as follows:

Together, we’re creating a community for female, tenure-track faculty at colleges and universities in the United States so we can have open, honest, and productive conversations about our careers and lives.

Who belongs—and who doesn’t—is unambiguous.

Process

Process—the manner and frequency in which we engage with each other—represents the infrastructure of a community. Good infrastructure can help a community thrive. However, creating infrastructure that doesn’t serve the objectives of the community’s members is akin to building a highway to nowhere.

An underutilized boulevard in Naypyidaw, the planned capital of Myanmar—a mismatch between infrastructure and community.

The Problems with Sponsorship

When I say sponsor, I’m speaking about a person or, more likely, an organization that underwrites the cost of building and maintaining the infrastructure that underpins a community. The larger or more established the sponsor, the greater the likelihood that its objectives aren’t aligned with those of its individual members. That’s a problem because it often leads to attempts by the sponsor to coerce its members.

In another article (I’m telling you, he’s on a roll), Fabian notes:

Often the use of force is well-intended and hard to distinguish from more positive qualities. Where exactly is the line between persuasion and encouragement? I sense the difference lies in our attitude towards the person we’re talking to. Are we trying to help them clarify their own reasoning or are we trying to push them towards our desired outcome?

This is true for non-profit as well as for-profit sponsors, albeit in different ways.

Over-reliance on Altruism

Psychologists recognize healthy selfishness and pathological altruism. Nevertheless, we tend to view altruistic behavior as unambiguously good and decry selfish behavior. I expect this may be particularly true in the context of communities sponsored by mission-driven organizations. Writing of his own experience attending a gathering hosted by a non-profit, Fabian confessed:

We both felt like we had to hide our true intentions of being there. We felt it would be disrespectful to the conveners to tell them that our true motivations to show up were driven mostly by the interests of our own projects versus the stated purpose of the gathering.

Our superpower as human beings is our ability to collaborate. From time to time, we will willingly subordinate our personal objectives in order to further the goals of the community. However, when faced with extrinsic pressure to conform, we’ll leave or withhold our full engagement.

An Unhealthy Propensity to Pitch

When we asked prospective members of Never Say Sell, a business-oriented community, what they didn’t want, here’s what they said:

Pitchfest and posturing

Spamming

Cold and obvious pitching

Pitching sessions

I could do without people selling their services or products during sessions about true business management/development.

Being sold to. We’ve been in a number of communities that were little more than prospect pools.

Community leaders using the platform for self-promotion.

See a pattern?

Obviously, too many for-profit sponsors conflate a community with an audience. If the content is good enough, people will tolerate advertisements as members of an audience. However, they won’t invest their intellectual and social capital in a would-be community that doesn’t serve their needs.

Strategies and Tactics

My business partner, Laura Black, and I have gleaned the following strategies and tactics from the preceding:

Focus on Membership-based Communities

My friend and collaborator, Tom McMakin, once told me, “Profit means you get to keep doing the work.” Hosting a community has a cost that needs to be covered to sustain the community. We view profit as a constraint rather than an objective. Generating revenue from membership fees represents a feedback loop that helps enforce the alignment of interest between the members and the host.

Ask Lots of Questions…and Listen Hard

We’ve learned the hard way that it is dangerous to presume we know what members want over time. We seek ways to find out through interviews, feedback forms, and surveys. More than anything, though, we try to listen hard to what is said.

Start Small and Grow Organically

In the long-run, membership-based communities depend on member-initiated referrals. That only happens when members are very satisfied with their experience. That means finding your core group and co-creating the community with them. Doing so takes time and patience. You must have a lot of conviction regarding your community’s purpose and potential to stick with it.

Additional Reading

Do we undervalue the role of personal interest in purpose-driven communities?

Build an Audience and Cultivate Community

Network vs. Audience vs. Community

Applying force in community doesn’t work

How Might Starting with Small Group Conversations Lead to a More Successful Community?