How Might We Stimulate Broader Participation in Our Conversations?

The degree to which status and quality are perceived to be linked drives the likelihood of actively engaging in social networking. Meritocratic cultures probably enhance the coupling of status and quality. That can actually inhibit the participation of low-status persons in collaborative communities. That’s a problem. Complex challenges are best tackled with cognitive diversity. That suffers when the conversation is limited to people who are high-performers along similar dimensions. If we wish to cultivate equitable and valuable communities, we need to find ways to help people identify and articulate the unique value they bring to the conversation.

We at Human Scale Business are dedicated to cultivating collaborative communities that provide access to insights and opportunities. Naturally, we’re interested in understanding the factors that discourage participation. So, the headline in the Kellogg Insights newsletter caught my eye:

Why Are Some People More Reluctant to Network Than Others?

The benefits of professional networking are backed by research, anecdote, and career coaches galore—and yet a lot of people shy away from it. A global survey of nearly 16,000 LinkedIn users revealed that while nearly 80 percent of professionals consider networking crucial to career success, almost 40 percent admit that they find it hard to do.

An easy explanation might be that 25 to 40 percent of the population are introverts who find social networking off-putting and exhausting. However, I’m an introvert who has systematically engaged in social networking over the course of my career. The easy explanation may not be an explanation at all.

A Focus on Agency

The Kellogg Insights piece summarized a paper co-authored by Jiyin Cao, a professor at Stony Brook University. She describes her research as being at the intersection of trust, technology, culture, and social networks. Professor Cao and her colleague took a fresh look at a familiar question:

Why do high-status people have larger social networks than do low-status people?

Previous research highlighted two extrinsic factors:

- High-status people are embedded in advantageous social networks.

- High-status people attract outreach from others.

In my interview with her, Cao explained that her work focused on high-status people’s agency and intrinsic characteristics that encourage some—but not all—to engage in behaviors conducive to building social networks over time.

Self-Perpetuating Hierarchy

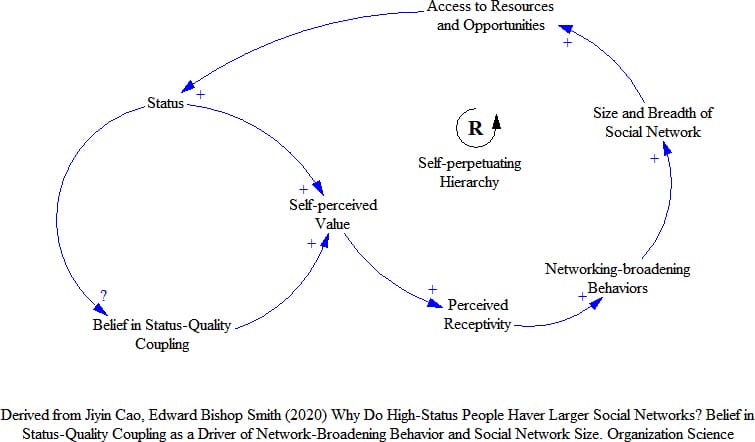

The following is my interpretation of Cao’s research in the form of a causal loop diagram:

- An increase in status causes an increase in self-perceived value. That is, high-status people tend to believe they have something meaningful to contribute to the contribution. (I’ll come back to this assertion in a moment.)

- An increase in self-perceived value increases perceived receptivity. In other words, if you believe you have something to contribute, you are less fearful that your social outreach will be rebuffed.

- As your perception of receptivity increases, so does the likelihood that you’ll actively engage in networking.

- Over time, active networking broadens and deepens your social network.

- Having a larger and more diverse social network improves your access to resources and opportunities.

- Such improved access helps boost your status.

This reinforcing cycle can be virtuous: high status begets high status. It can also be vicious: low status yields low status. Left unchecked, hierarchy and inequity can be self-perpetuating.

A Caveat

Cao’s research identified a key factor that I breezed by in the preceding:

Status translates into self-perceived value to the extent of one’s belief that status implies quality.

Cao calls this status-quality coupling. If you believe your current professional status is an accurate reflection of the merit of your ideas and experiences, you will be more (or less) willing to engage in networking.

- High-status people who believe their status is earned will reinforce their status through active networking.

- Low-status people who believe their status reflects a limited capacity to contribute will not engage in networking, and they risk social stagnation.

Business culture—maybe particularly here in the United States—emphasizes meritocracy and, consequently, status-quality coupling. There are at least a couple of variables that confound that narrative, though:

- Success and the status it confers is a function of skill AND luck.

- We tend to ascribe quality to people who look, think, and have backgrounds similar to our own. We often define “quality” very narrowly.

An Opportunity

So, how might we encourage broader participation in our conversations? How might we decouple one’s (current) status and one’s perceived ability to contribute?

Cao describes a “growth theory” of relationships. People who espouse a growth perspective reject the notion that because “We’re just not the same kind of people. It just wouldn’t work.” That leads her to perceive an opportunity:

If we are able to train people to have this growth theory mindset, people are more likely to overcome the tendency to choose similar people to collaborate [with] or to be friends. I think it could be a really effective and promising intervention to create a diverse network.

In other words, adopting a growth mindset regarding our relationships opens the door to embracing a broadened definition of quality and our individual capacity to contribute.

The Best People Don’t Always Mean the Best Teams

Challenging our tendency to affiliate with those who are similar to us creates opportunities to invite broader participation in our conversations:

A junior marketing associate might not have very high performance because they don’t have a lot of experience. On the other side, they can actually contribute a lot in terms of cultural knowledge about what’s going on. Once they realize they have this kind of value to offer, this sense of self-value can help them to feel more comfortable to network.

This is not just about creating a more equitable playing field. Cognitive diversity yields superior performance in a complex world. When tackling hard problems, the highest performing teams aren’t composed of the best people when their abilities are similarly defined. As Scott Page, a researcher at the University of Michigan, says:

Diversity trumps ability.

Culture (Probably) Shapes How We Think About Networking

Page emphasizes that cultural identity is not equal to cognitive diversity—but the former shapes the latter. I suspect Cao would agree. At the conclusion of my interview with her, she described her most recent work:

Do we have some different types of metacognition of networks? I think it might have something to do with the culture we grow up with. For example, people will describe U.S. people’s social networks as being very loose…In contrast, the East Asian type of network…is a very tight network…What I want to study is [will these] two kinds of culture [lead] to different kinds of network metacognition?

Simply put, does the culture in which we are embedded shape how we think about networking? I look forward to hearing about what she learns.

Translating Ideas Into Action

Here are my takeaways from my conversation with Professor Cao:

- Although they might have the most to gain, rookies may be less likely than veterans to participate in a collaborative community. Rookies might not believe they can contribute sufficient value to the conversation.

- Diversity trumps ability. The most valuable collaborations stem from cognitive diversity. Cultivating such diversity is difficult, but advocating a growth perspective on relationships makes achieving such diversity more likely.

- One of our key roles as hosts of collaborative communities is to help prospective members recognize and articulate the unique contributions they can make to the conversation.