We often underestimate the time it takes to bring on a new employee. After all, we’re motivated to hire because we need to increase our delivery capacity. What transpires, however, is often a slower-than-expected up-to-speed time for the new worker—alongside a longer-than-expected hit to our own productivity. Giving and getting feedback effectively can accelerate the learning needed to help new employees help you.

The 5 Why’s

Ways of doing work that seem obvious to us may be foreign or peculiar to unfamiliar eyes. When explaining our business processes and procedures, we can usefully volunteer the why as well as the what. By encouraging colleagues to use the 5 Why’s (the process of asking Why? multiple times to discover underlying causes), we can make explicit the motivations and values on which our work processes are built.

It may seem childish, but asking “Why?” several times in succession helps to uncover root assumptions driving our understanding and actions.

The first levels of Why might reveal the process intent:

- Because we want to document conversations with clients

- Because we want to refer back to notes at regular intervals

- Because we want to ensure we consistently meet clients’ needs and don’t drop any of their concerns over time

Continuing to ask or explain, “And why is that?” may surface underlying values:

- Because we want to be true to our word

- Because we value the depth and breadth of the work we can do when we have long-term relationships with our clients

Asking and explaining Why multiple times not only provides broader, richer contexts in which new employees learn your business operations, but also invites them to contribute new approaches to help the business live out its highest values in innovative ways.

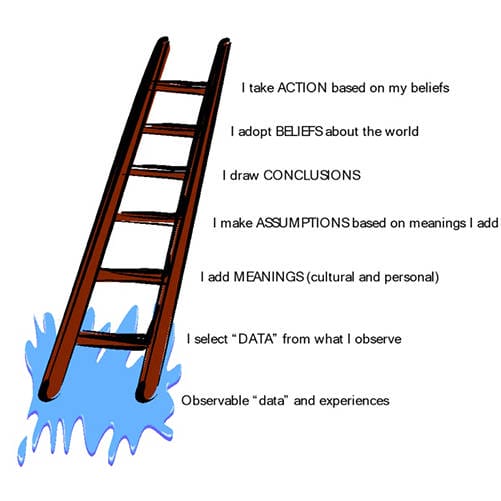

The Ladder of Inference

Working with new employees offers the chance to innovate but also to create many mistakes. The Ladder of Inference is particularly useful when we need to acknowledge and address a misunderstanding.

As a metaphor, the ladder helps us recognize how quickly we scale the rungs from directly observable data to inferences and judgments. When we recognize errors in another’s work, often we attribute, “She just wasn’t listening when I gave instructions” or “He isn’t conscientious in his work.” Rather than open an error-addressing conversation with such a high-rung attribution, it can be useful to start with the observable data—and also a combination of assertion-and-question. “When I was working with this file, I didn’t find the…Did I miss it?” Gradually working up the rungs of inference, the conversation might continue by describing your recall of the instructions you provided and your expectation, along with, “Was I not very clear? I know sometimes I jump around when I’m explaining something.”

This process of beginning with data-all-can-observe usually heads off the least charitable attributions in ourselves and often reveals really admirable purposes and honest miscalculations in others. And when we find ourselves in a high-on-the-Ladder-of-Inference argument (which sounds like, “Did not!” “Did, too!”), we can take a break and then return to the conversation with questions that back us all down our inferential rungs to something—observable data, worthy intentions, information that hadn’t yet been shared—offering common ground from which to work again.

Benefits and Concerns

I have used Benefits and Concerns in such a wide variety of contexts that I’m convinced its simplicity belies its usefulness.

The simple act of capturing benefits and concerns has an outsized impact on the quality of our conversations.

Pragmatic Bs and Cs

When working as a project and program manager for a large company, I made sure we ended every project meeting by first asking for Benefits:

- What was good about the meeting?

- What accomplished milestones since the last meeting should we acknowledge?

And then I elicited Concerns:

- What do we need to be thinking about as we move forward?

- What concerns remain unresolved?

For each Concern, we identified Next Steps with three Ws:

- Who would do

- What by

- When

The process took about 5-10 minutes of a 60- or 90-minute meeting, longer if we had been working together all afternoon or all day. I always included our Bs and Cs and Next Steps with the meeting documentation.

By asking my colleagues to help make explicit these aspects of our work-in-process, I helped reinforce their engagement and commitment. We left a working session with clarity about what we had accomplished (even if the “accomplishments” centered on identifying ill-considered assumptions and misunderstandings!) and agreed-on allocations of responsibilities for the next steps. And we always began the next project meeting with updates on the who-was-doing-what-by-when from the previous meeting. Over time, these Benefits and Concerns and Next Steps provided cumulative insights into what we had learned as we had worked on complex cross-functional initiatives that affected multiple aspects of information systems, marketing, and operations.

Strategic Bs and Cs

Even more valuable, when my firm had employees we used Benefits and Concerns as the structure for performance reviews. The employee and two principals independently created and documented lists of Benefits and Concerns about the employee’s work, and we began the review conversation by sharing round-robin our perspectives. Then, for every Concern, we collectively identified the next step and who would do what by when. Rather than a perfunctory or unpleasant required task, which is how we each had experienced performance reviews at other organizations, everyone found both the preparation and the conversation generative.

I believe we found using Bs and Cs in this way energizing because the approach placed emphasis on learning, engagement, and ongoing collaboration in accomplishing the business’s aims. As a principal, I found this relieved the pressure to use compensation as the primary means for expressing value and appreciation. Instead, I found that my employees most valued opportunities to apply their growing skills in broader and deeper ways—and I didn’t have to think of all those ways, as they had plenty of ideas. Bs and Cs kept the focus on what really mattered to all of us: helping each other develop professionally in ways that could benefit us all for a long time, regardless of how the future might unfold.

The Benefits of Constructive Feedback

Tools for constructive feedback are key to collaborative learning. When we bring new people into our business, we usually place emphasis on their learning. But by engaging in conversations of constructive feedback, we inevitably learn, too—about ourselves, as well as about new possibilities for seeing and doing the work. While it’s costly to engage in a hiring process, losing a good colleague is even more costly. And the opportunity to retain and continue working with people we enjoy? That’s priceless.

Key Ideas

- Reinforcing feedback means, “Do more of this.” Balancing feedback means, “Do less of this.” Both types of feedback are required to learn and adapt efficiently.

- The 5 Why’s technique helps uncover root assumptions, motivations, and values. By making them explicit, you can test and manage them.

- The Ladder of Inference can help us acknowledge and address miscommunication.

- By using the Benefits & Concerns debrief technique, you can keep the focus on what matters and elicit actionable reinforcing and balancing feedback.